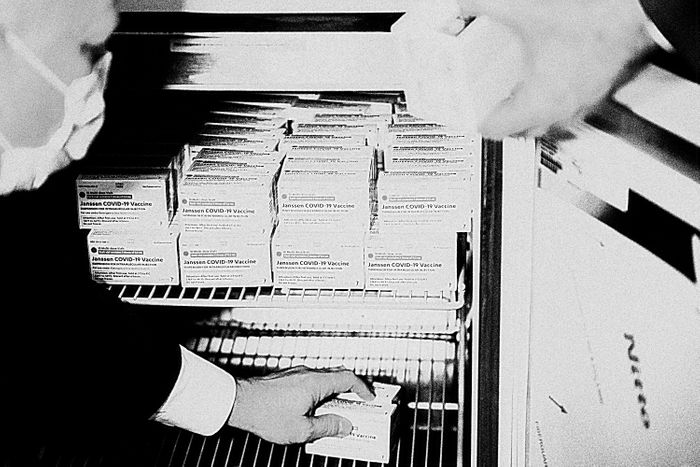

The Story of One Dose

Inside the sprawling operational puzzle of bringing the Johnson & Johnson COVID vaccine to the public.

Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer/Shutterstock / M-Foto

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

As

an object, it’s not much: an inch and a half of glass with a stopper

and some liquid inside. But a thimbleful of the stuff has amazing power —

the ability to liberate us from our yearlong collective trauma. The

fact that it’s available, scarcely a year after the start of a pandemic,

is both an industrial miracle and a freakish stroke of luck; a decade

ago, technology did not exist that could bring vaccines so quickly to

the public’s arms.

Pfizer

and Moderna crossed the finish line first, neck and neck, in December.

The third and most recently approved vaccine was from Johnson &

Johnson. The J&J vaccine holds some crucial advantages:

Only one dose is required rather than two, and while the other approved

vaccines expire 30 days after thawing, Johnson & Johnson’s lasts

three months, making it easier to distribute in countries that lack an

advanced cold chain. The story of the vaccine’s path from development to

mass distribution is a lesson in the power of the global capitalist

system — the network of corporations and supply chains that, though it

can suffocate and disempower us as individuals, can also summon forth

immense material and intellectual resources and deploy them for the

greater good.

From

the start, J&J struggled to catch a break. The pharmaceutical giant

played it safe during development and lost crucial time, failed to get

FDA approval for parts of its U.S. production chain, missed several

delivery targets, and wound up with a vaccine that underperformed its

rivals in clinical trials. Then, another obstacle: Last week, the New

York Times revealed that the new batch J&J had pledged would be delayed even further, after a mix-up at a subcontractor’s production facility ruined 15 million doses. The Biden administration has since directed J&J to take over every aspect of vaccine production at the plant.

The setback was significant, but not fatal. The facility where the mix-up occurred was

part of a production process that relies on a precise orchestration of

timing, engineering, and logistical expertise across multiple

continents, which makes it vulnerable to bad luck and human error. But

the system is also resilient: When the batch of J&J doses was

compromised, alternative supply lines were available to compensate for

the failure. Here is how that entire tempestuous journey unfolded — the

breakthroughs, the setbacks, and the way the pieces came together to

bring vaccines to millions of arms.

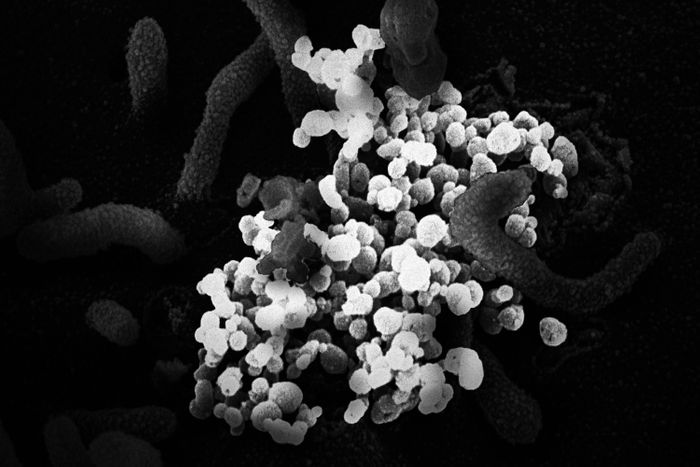

Photo: IMAGE POINT FR/NIH/NIAID/BSIP/Un

On

the afternoon of January 3, 2020, a box arrived at the laboratory of

the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, a complex 30 miles southwest

of the city center. The box contained swabs taken from a patient in

Wuhan who had fallen ill with a new kind of pneumonia. Worried about how

dangerous the new pathogen might turn out to be, the Chinese government

had banned medical researchers from publishing any information about

it. China had experienced public-health scares before: Between 2002 and

2004, a deadly and highly infectious virus called SARS had spread

through the country. It was in response to SARS that the Shanghai Public

Health Clinical Center had been built.

Zhang

Yongzhen, the laboratory’s leader, was a specialist in assessing new

viruses. Over the next 40 hours, his team painstakingly broke the

genetic code of the new pathogen into its sequence of nucleotide base

pairs — essentially decoding the software that the virus plugged into

its host to make copies of itself. The sequence would tell researchers

exactly how it worked so that they could figure out how to thwart it.

At 2 a.m. on January 5, according to a profile in Nature,

one of Zhang’s team members gave him bad news: The virus was a close

relative of SARS. Though little was yet known about how the disease

progressed or how it was transmitted, the potential for rapid spread and

widespread death was real.

On

the morning of Saturday, January 11, Zhang was on a plane about to take

off for Beijing when he got a call from Edward Holmes, a virologist

from the University of Sydney. Holmes, a longtime colleague of Zhang’s,

knew that he had sequenced the virus’s genome. Holmes impressed upon his

colleague the importance of publishing the information. Zhang asked for

time to think. If the new disease was as contagious as SARS, it could

spread beyond China and put the whole world at risk. But there was a

more immediate hazard: the danger of angering Chinese authorities. An

airline attendant appeared and told Zhang that the flight was about to

take off. He had to decide. “Okay,” Zhang said. Holmes could release the

sequence data.

In

Boston, on the other side of the international dateline, it was still

Friday, January 10. Dan Barouch, a virologist at the Beth Israel

Deaconess Medical Center, was hosting an off-site meeting with his lab

at the Boston Museum of Science, in a room that enjoyed a view of the

Charles River. Barouch and his team had gathered to plan for the year

ahead, but everyone was discussing the news from China, where the first

death linked to a new form of pneumonia had just been announced. “It had

all the hallmarks of a virus that we thought might have pandemic

potential,” Barouch recalls.

In

some ways, this was the moment Barouch had been preparing for. For the

last decade and a half, he and his team had been developing a “vector” —

a way to sneak part of a pathogen’s genetic code into human cells. Once

there, it would trigger the cells to create pieces of the pathogen for

the body’s immune system to identify. Their vector was a variant of an

adenovirus, a bug that causes the common cold. Called Ad26, it had had

several of its genes removed so that, while it was able to insert itself

into human cells, it couldn’t reproduce and make a person sick. But it

could still merge with the human host cell and bring with it the

pathogen DNA needed to cue the immune system. This approach could

theoretically work with almost any infectious agent — Barouch’s team had

already used Ad26 to make vaccines for HIV, tuberculosis, and Zika.

Pfizer and Moderna would follow a similar technique using mRNA; by using

DNA, a more stable nucleic acid, Barouch & Co. were crafting a

vaccine that could be injected in one dose.

It

was Friday evening, Boston time, when Zhang’s data hit the internet.

Zhang’s lab had decoded the virus into letters symbolizing the four base

pairs that make up its genetic code: A, C, G, and T. In effect, Zhang

and his team had compressed a living thing into pure information. By

uploading it, they had transformed it again, into a string of ones and

zeros split up into packets that bounced around the fiber-optic nodes of

the internet. Barouch and his team went to work. On Monday, they began

translating Zhang’s digital data back into nucleotide sequences, which,

in turn, could be converted back into an actual virus. It was as though

pieces of the coronavirus had teleported through the web.

Immediately,

Barouch saw the best strategy. He noticed that the virus contained a

spike protein — a piece that sticks out like the rubber hair on a Koosh

ball, which an antibody in the human bloodstream would be most likely to

recognize. From the genome, Barouch could tell which stretch of DNA

coded for it. To make the vaccine, this would be the sequence to pack

into the Ad26 vector. The question was what exactly the message should

contain: the whole spike protein sequence or just part? Should the

scientists include a preamble, or other sections that might help get the

message across to the immune system? The decision could mean the

difference between an efficacious vaccine and a useless one.

Meanwhile,

the disease was spreading rapidly in China and cases were starting to

appear internationally. Barouch contacted Johan Van Hoof, the head of

vaccine development at Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a subsidiary of Johnson

& Johnson with R&D centers in Leiden, the Netherlands. They had

worked together on vaccine development for more than a decade. “Johann,

this is looking bad,” Barouch told him. “I think we need to make a

vaccine.”

“Absolutely,” Van Hoof said. “We do.”

Photo: Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe

The

labs in Boston and Leiden began working in parallel, staying in touch

with daily phone calls. They started by creating a dozen different

lengths of DNA and injecting them directly into mice to see which

triggered the most vigorous immune response. They then winnowed the list

to seven candidates, packed them into the Ad26 vector, and tested the

variants on Rhesus monkeys. It was a bit like A/B testing of different

versions of an Internet ad: Each version of the DNA snippet would cause

the body’s cells to produce a different protein, which, in turn, would

have a different effect on the immune system. They wanted to make sure

they chose the most powerful one.

On

February 11, the worldwide death toll passed 1,100, with more than

44,000 cases reported in China and several other countries. Health

officials at last gave the disease a name: COVID-19. In those crucial

early months, every day in the lab presented an existential battle

between quality and speed. If Barouch and Van Hoof made a best guess at

the right sequence and put it straight into the vector, they could roll

out the vaccine sooner and save countless lives — the approach that

Moderna and AstraZeneca chose. But this could result in an inferior

vaccine that would allow more people to die. In the end, the scientists

decided to take a few months to test multiple versions on animals first,

then advance the most effective one to human testing.

They

ran the test on 52 animals. Some of the variants were given to four

animals, others to six. The researchers then exposed all the test

animals to COVID. Compared to control animals, the monkeys that received

versions of the vaccine showed little viral replication. But monkeys

that received a variant called S.PP showed almost no sign of infection

at all. On March 30, 2020, it was this variant that Janssen announced as

its vaccine candidate. It was called Ad26.COV2.S.

To

ensure that the Ad26.COV2.S would be safe and effective for humans, the

company would need to test it — first on a few hundred people, then on

tens of thousands. It normally takes years to conduct a full slate of

tests, get results, and design a follow-up round. Instead, Van Hoof’s

team began running steps in parallel. As soon as it could see what

direction the animal tests were going, the lab started to produce

vaccine material for human trials — a decision that would move the trial

start date up from September to July. And, in April, even before the

results of the clinical trial came in, Johnson & Johnson began

making plans to manufacture and package the vaccine at scale, so that

mass quantities would be ready by the time the human tests came back. If

the results were good, J&J could quickly start putting needles in

arms. If not, the vaccines would get chucked in the trash, and billions

of dollars spent on research and development would go up in smoke.

Months later, Johnson & Johnson learned it had made the right call. Clinical-trial results showed the vaccine worked and was safe, and it received a green light from the FDA in February 2021.

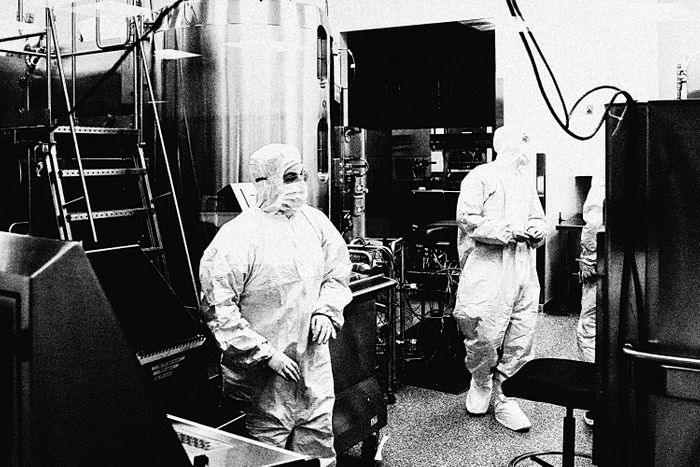

Photo: Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post

Johnson

& Johnson makes a wide variety of medications, but it had never

fulfilled an order as large as the coronavirus vaccine, a drug that 7.8

billion people — 331 million in the U.S. alone — needed right away. By

spring, the Trump administration was lobbing contracts at

vaccine-makers: $483 million to Moderna, $456 million to Johnson &

Johnson, $30 million to Sanofi, then $1.2 billion to AstraZeneca, and

$1.95 billion to Pfizer. Johnson & Johnson promised 100 million

doses, but even that was way beyond its capabilities. So to augment

production from Janssen’s own facility in Leiden, it signed up partners

around the world to produce its as-yet-unproven vaccine, including, in

the U.S., a company called Emergent BioSolutions.

Founded

in 1998 to produce anthrax vaccine as a defense against terror attacks,

Emergent had, over the years, received hundreds of millions of dollars

to provide doses for the U.S. government’s strategic stockpile. When the

threat came in the form of a pandemic, it was tasked, instead, with

manufacturing millions of doses of Ad26.COV2.S. But growing Ad26 viral

vectors wasn’t a straightforward process. To turn the original virus

into a harmless vaccine, researchers had deleted genes the virus needs

for replication; in order to make copies of itself, the Ad26.COV2.S

vector required a special environment. The solution was to insert the

virus’s missing genes into a unique human-cell line that had originated

in the eye of a human fetus aborted in the mid-1980s. This genetically

modified cell line was named PER.C6. Unlike normal human cells, which

can multiply only so many times before dying, these cells are immortal;

as long as they’re fed the right nutrients and kept at the right

temperature, they can grow forever. Because PER.C6 contained the genes

that Ad26 needed to reproduce, it held the key to growing the viral

vectors.

Last

fall, in an office park in East Baltimore, Emergent technicians added

the contents of a cell-culture bag to a ceiling-high tank holding a

single-use bioreactor. The bioreactor was filled with a 1,000-liter

solution of sugars, proteins, and other nutrients. Inside the warm bath,

cells began to multiply.

Once

the PER.C6 cells grew to the right volume, workers added several liters

of Ad26.COV2.S seed containing millions of vector particles. Inside the

bioreactor was a genetically engineered paradise. The adenovirus

particles latched onto the exterior of PER.C6 cells and injected them

with their DNA. Once inside, the genetic material caused the cells to

start manufacturing the components that make up the virus particle,

until the hosts were so stuffed with tiny self-assembled machines that

they burst, spewing out a conquering robot army into the broth. After a

week, the PER.C6 cells were either hijacked or dead,

and the tank contained quadrillions of virus particles, enough for

millions of doses. Waste and cell fragments got filtered out, and what

was left was concentrated, then frozen at 94 degrees below zero. The

resulting material is known as vaccine substance.

For

months, this process took place again and again in Baltimore and in the

Netherlands. But by early 2021, the millions of units of vaccine

substance produced at Emergent still weren’t allowed to leave the plant.

Like Moderna and Pfizer, J&J, under the pressures of a global

crisis, had begun activating parts of its supply chain before all of

them had received the official green light, and the FDA had not yet

inspected and approved the Baltimore facility, which had, in recent

years, received a string of citations for quality-control issues.

Then,

in late February, disaster struck. Emergent accidentally mixed Johnson

& Johnson vaccine ingredients with those of AstraZeneca’s,

destroying 15 million doses and further delaying the facility’s FDA

approval and the delivery of more vaccines. The plant had caught the

error and quarantined the incorrect doses, and, in the meantime, a new

supply line was starting to get under way — in March, President Biden

announced that the pharmaceutical giant Merck, which had abandoned its

own vaccine initiative, would convert and upgrade its facilities to help

manufacture more J&J doses. But until it could sort out the mess,

Johnson & Johnson was forced to rely on vaccine substance produced

at Janssen’s plant in Leiden.

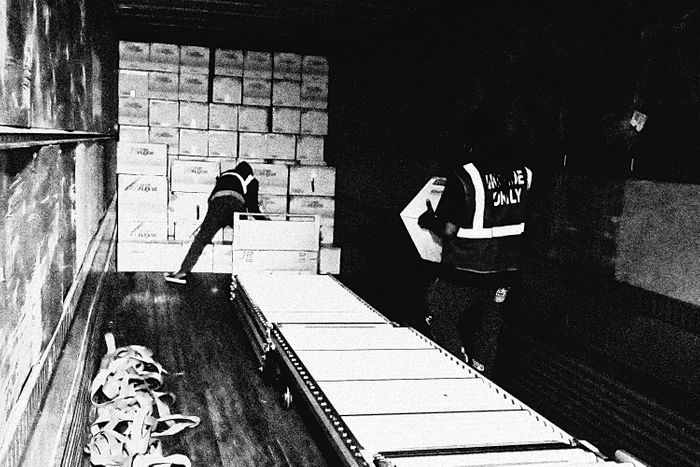

Photo: Catalent Pharma Solutions/Youtube

After

the vaccine substance is manufactured and approved, it then has to go

to a “finish and fill” facility, where the deep-frozen concentrate will

get turned into stuff that can actually be injected into a person. Last

year, J&J scrambled to contract with Catalent Biologics, an

international pharmaceutical processing company that could quickly

expand its plant in Bloomington, Indiana. In June, Catalent was also

tapped to finish-and-fill the Moderna vaccine.

Inside

a space that, a year ago, was an empty warehouse, gleaming panoplies of

stainless-steel arms and wheels whir. Behind aseptic barriers, the

vaccine substance is thawed, blended with substances like

2-Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (to improve its solubility) and

Polysorbate 80 (a stabilizer often used in food and cosmetics), then fed

into a vial-filling assembly line. Sterilized vials move by conveyor

belt into a filling station where a multipronged needle bobs up and

down, squirting ten full at a time.

There

is no margin for error. A single vial that gets chipped or cracked

could ruin an entire production run. Optimizing this kind of process is a

never-ending task, with chemists and engineers tuning and tweaking at

the nano level. The material sciences company Corning, for instance,

recently figured out how to prevent glass from flaking off vials by

switching from borosilicate to aluminosilicate, a substance it calls

Valor Glass.

Each

newly filled vial contains five doses — about a quarter-trillion

adenovirus particles in three milliliters of liquid. A printer lays an

alphanumeric code around the vial, then a robotic packing machine places

ten vials in a box, at a rate of 600 vials a minute. During the filling

process, no human hand has intervened once. As with Emergent,

Catalent’s new facility needed an FDA signoff before the material it

produces could be released to the public — on March 23, 2021, that

approval finally arrived. Five days later, the Bloomington plant began

shipping out J&J vials, which could then join the 6 million finished

vaccines that had been sent to the U.S. from J&J’s Netherlands

factory.

Late

last year, a billboard appeared along the highway in Shepherdsville,

Kentucky, a rural town 20 miles south of Louisville. “NOW HIRING,” it

said. “Material Handlers Get Paid Up to $20.12 Per Hour.” The jobs were

posted by McKesson, a large pharmaceutical-distribution company that had

been contracted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to

package and dispatch all COVID-19 vaccines, except for Pfizer’s. In late

2020, the company completed construction on its brand-new

Shepherdsville facility, a squat, quarter-mile-long million-square-foot

warehouse, and it needed to hire more than 500 workers.

In

the race to create and distribute the vaccine, McKesson’s role may

first appear as mundane as that of any fulfillment center: It’s tasked

with counting out the correct number of ten vial-size boxes for each

site (900 vaccine doses to a high school in Kalamazoo, Michigan, say, or

300 to a health center in Athens, Georgia) and packaging them into

cartons for shipment. But it’s the scale of the operation that’s key — a

huge portion of America’s vaccine production will, at one point, need

to go through McKesson. Its Shepherdsville hub is one of the company’s

four facilities shipping COVID vaccine doses; to construct the storage

racks alone required at least 3.7 million pounds of steel, more than a

quarter of the metal frame used to construct the Eiffel Tower.

Inside

a hangar-like room hung with American flags, workers load the boxes of

J&J vaccines into KoolTemp EPS coolers, adding frozen gel packs and a

monitoring device that logs the temperature and triggers a warning if

it gets too high or low. To prevent that from happening, workers are

allotted 30 minutes to place the coolers into cartons. (In another

section of the facility, Moderna doses, which must be maintained at a

lower temperature, are packed inside a freezer by workers wearing parkas

and insulated boots.) McKesson workers are also tasked with assembling

the kits that contain everything a vaccination center needs to

administer the vaccines: alcohol pads, face shields, surgical masks, and

needles and syringes.

Less than two days after arriving at the McKesson warehouse, the vaccine is off on the next leg of its journey.

A

UPS semi pulls up to the loading dock, and workers place the KoolTemp

cartons into the trailer. The truck swings onto the onramp to I-65 North

and drives the 20 miles to UPS Worldport, a 5.2-million-square-foot

intermodal shipping hub located on the grounds of Louisville Muhammad

Ali International Airport. There, the boxes are unloaded, scanned, and

sorted through a 155-mile-long system of conveyor belts.

Until

now, each stage of the vaccine-making process has required some kind of

scientific or logistical coup: the compression of a years-long process

into a matter of weeks, the creation of a new technology, the rapid

alteration of a physical landscape. But when it came time to move those

millions of doses to their final destinations, it took barely any extra

effort for UPS and FedEx to activate their networks. After all, among

the 20 million packages delivered daily, thousands of vaccine shipments

were a rounding error.

In

2019, UPS introduced a service for health-care customers that allows

them to more precisely track shipments of medicines, samples, and

vaccines. Each carton is affixed with a tag that allows sensors to track

its location, and the data gets transmitted to the UPS health-care

command center inside Worldport, a room with four large-screen monitors

on the wall displaying national weather and UPS flights in transit. When

bad weather before Christmas meant that a vaccine shipment’s

destination was closed, for instance, the health-care command center got

on the phone and arranged to have it redirected.

Photo: Timothy D. Easley/POOL/AFP

As

the cartons wend their way through the maze of conveyor belts, scanners

read the label on each and shunt it to the appropriate outbound loading

station. Shortly before midnight, planes start arriving at the

Louisville airport at the rate of about one a minute, carrying inbound

packages; those packages get sorted at the rate of 115 every second,

then loaded back onto planes heading for their final destination.

Within

15 minutes of its unloading at Worldport, a box slides down a chute to

the outbound station. A worker scans it and checks all six sides for

damage, then loads it into an airfreight shipping container bound for

New York. Around 4 a.m., the pilot takes off.

Photo: Johnny Milano/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Later

that morning, the box arrives at the loading dock of a vaccination

site. This final leg of the vaccine’s journey — delivering doses to a

place where they can be put into people’s arms — is the simplest in

concept, but was, for a long time, the most vexing. In the weeks after

the first vaccines were approved and shipped, New York State proved

ill-prepared to deliver its allocated doses. By early January, some

vaccination sites had used less than 20 percent of the doses they’d been

sent.

Similar

problems played out across the country. Despite having lavished

billions on producing vaccines, the Trump administration had largely

ignored the question of distribution and administration, leaving the

matter to states and offering little support. Entire organizational

structures had to be built on the fly using whatever labor happened to

be available. In New York City, the effort leaned heavily on the Medical

Reserve Corps, a group of more than 15,000 volunteers who stand by to

help out in crises. By the end of January, the system was running

smoothly enough that the vaccination centers were efficiently doling out

what they’d received.

Photo: Angus Mordant/Bloomberg via Getty Images

When

it’s your turn, you roll up your sleeve. The nurse chooses a needle

based on the heft of your arm — an inch and a half for larger people, an

inch otherwise — and pushes the tip into the rubber gasket atop the

vial containing your dose. She slips the needle into your muscle. Inside

your arm, 50 billion genetically engineered nanoscale robot assassins,

carrying genetic payloads downloaded from the internet and bred in a

soup of immortal human-eye cells, begin prying their way through your

cells’ defenses.

One Great Story: A Nightly Newsletter for the Best of New York