Neurosurgeon

==============================================

Redoing what you thought you did perfectly can be an invitation for ego wear and tear and gossip . Here’s why this should not apply to reopening up wounds and other wisdom from the OT

“The dressing is not completely dry,” the doctor in charge of the floor informed me about Mary’s wound while I was on my morning rounds. We had operated on her back three days ago to relieve severe nerve compression. She also had significant spinal instability, which we had to fix by inserting some screws and rods. “I was going to discharge you today,” I told her, “but your wound doesn’t look great.” I peeled off the dressing to notice a yellowish soakage on it mixed with a tinge of blood.

“But I feel perfect!” she interjected. “On the outside,” I warned her. “We don’t know what’s going on inside.” I pondered at the deeply philosophical statement I had just made – and I wasn’t even a mental health professional. Oftentimes, we may seem unperturbed externally but there is a tsunami going on internally. I wondered if surgical wounds and human emotions had a similar modus operandi.

“It’ll settle down, won’t it?” she tried to convince me, eager to get back home. “Let’s dress it again and take a look in the evening,” I offered instead, because I don’t discharge patients if their wound isn’t dry. We took a swab from the wound and sent it for culture, starting her on antibiotics.

Very rarely do patients have some discharge from a surgical wound. This discharge is often superficial, originating from a little fat degenerating in the subcutaneous tissue, and it settles down on its own. Sometimes, if it’s infected, it could be pus, which is what one needs to be wary about, but that also often subsides with a course of antibiotics if it is depthless. It is the deep-seated ones we need to be cautious about. And like emotional wounds, we can’t tell the difference until it’s too late.

When I returned in the evening, the dressing was soaked a little more. It also had a slightly offensive smell to it, I realized, as I pulled the gauze off the wound and brought it to my nose to take a sniff, much to the disgust of the nurses and interns around me. “If it’s your mess, you must be ready to get your hands dirty. Only then will you be able to clean it up,” I gave them some insight, as the creases on their nauseated faces eased out. I pressed on the edges of the wound and the discharge was purulent.

“We have two options,” I told Mary. “Either we give you intravenous antibiotics and hope that it subsides, or we take you back to the operating room first thing tomorrow morning, wash it out, and then administer antibiotics.” Mary finally realized that this was getting serious. “What would you like to do?” she threw the ball in my court. “I don’t like not knowing what’s going on,” I said categorically. “Instead of allowing it to fester, it’s better to open it up, drain the pus, and clean it up,” I opined. “Infected wounds are like bottled up emotions,” I told her, doubling up as her shrink. “If you don’t make space for it, it’s going to blow up sooner or later, and that has a larger price to pay.”

Taking patients back to the operating room, especially in private practice, is considered taboo. It means acknowledging that something has gone wrong, which we need to fix. In the world of mental health, it is considered a step in the right direction, but in the surgical world, people – patients, relatives, colleagues, or administrators – will often scoff at you. It dents your reputation (as if that was ever a real thing) and everyone gossips about it (but it’ll never fall on your ears) that you didn’t do it right the first time around.

I’m very aggressive as far as opening up wounds is concerned. Especially if they belong to others. Especially if I’ve inflicted them. My theory is simple: If you’re going to war every day, you will have to take a few bullets. But with time and experience you get better at dodging those bullets. It’s not that they won’t strike you; they hit spots where it’ll hurt less.

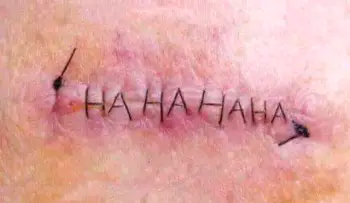

The next day, we took Mary back into the operating room, flipped her on her tummy and made an incision into the previous wound. Frank pus, the kind that results from an acute inflammatory reaction, came out under pressure. We cleaned the cavity with a bunch of solutions and washed everything out for it to look anew again. “I wonder where this came from,” my colleague asked while we were closing her back up. “However much you audit it, sometimes you’ll never know,” I replied. Just like our feelings, I thought to myself.

When she came for a follow up the next week, we removed her stitches. The wound was clean and dry. It had healed cleanly, with a small footprint of us having been there. “Scars are actually beautiful things,” Mary told me. “The hurt is over, the wound is healed,” she crossed her heart. “Amen,” I went along in the name of God. I’m glad we did the right thing. Over the past decade, I’ve taken several patients back to the operating room, and I promise you, it’s not because I’m a bad surgeon. Never have I regretted the decision.

Mary was the last patient I saw that day. And like most evenings before I leave, I put my feet up on my desk and cross them over to ponder for a few minutes on the day gone by. The first thought to strike – Why do I treat my own wounds so differently from those of my patients? What pain or doubt or fear am I concealing? Would I be okay ripping into my own wounds with that much ease, tearing them apart to examine them closer?

PS: I only speak metaphorically, of course, in case there are some kind hearted aunties out there wondering, “Beta, are you okay?”

I’m fine.

No comments:

Post a Comment